It has now been one year since the 60-day STRA (Short Term Rental Accommodation) cap was introduced into Byron Shire. This was a significant push by the council, which expended a considerable amount of political capital to get this over the line. The proposal did have widespread community support. However, it appears that not much has changed, and the intended outcome of increasing the housing stock and rental pool has not been achieved.

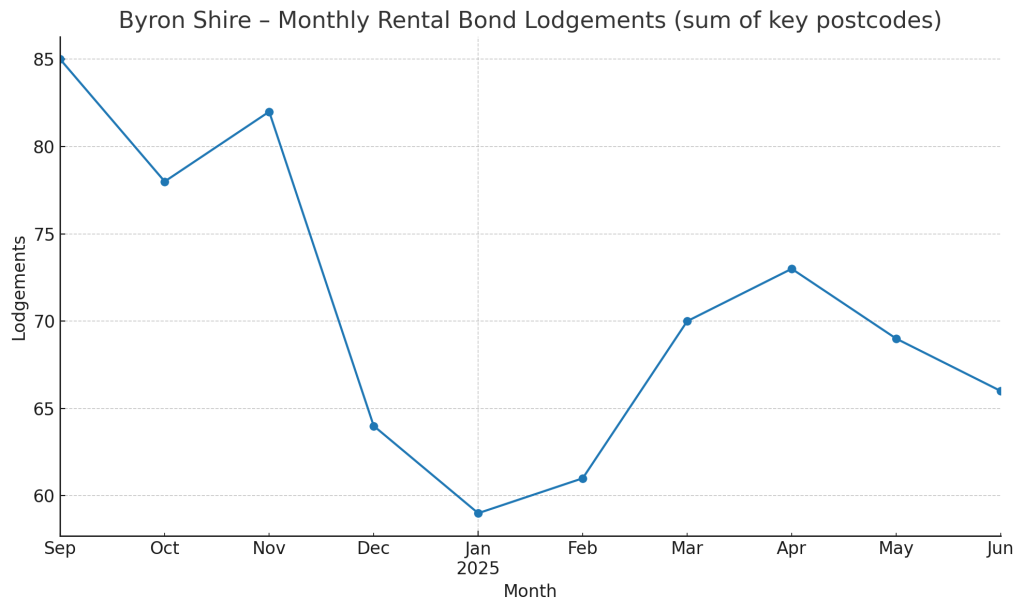

A recent report, undertaken by the Sydney University’s School of Architecture, Design and Planning, shows that Short-Term Holiday Rental (STHR) platforms have maintained, if not improved, their rental market share in all NSW coastal towns. This is after the 180-day cap was introduced in NSW and the 60-day cap in Byron Shire. The graph below shows the number of lodgments to the Rental Bond Board in Byron Shire over the past year. It clearly shows a noticeable decline in rental vacancies, even with the 60-day cap in place.

Although it may be too soon, early indications suggest that the hoped-for outcome did not eventuate.. Many people within the hospitality industry predicted this would happen. Holiday Letting (HL) operators were surveyed before the legislation was introduced, and many stated that they would either work around it, abide by the 60-day cap, or use their property only for themselves when on holiday, leaving it vacant for most of the year (the worst possible outcome). Very few said they were going to permanently let their property. Even if it had created more rentals, most STRA properties are upmarket and unlikely to address the lower-level housing shortage.

Was it worth it?

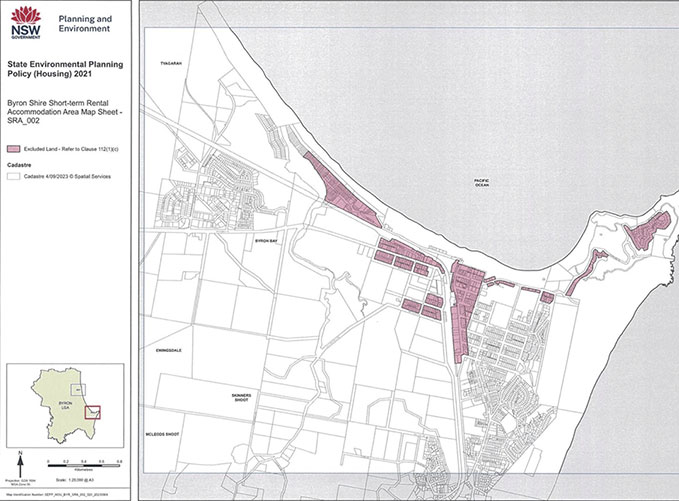

There was no doubt that the STRA industry in Byron Shire required regulation. The number of local homes being converted to platforms like Airbnb needed to be kept in control. However, I believe the quoted 17% of homes in Byron Bay used for HL, as noted in this report, is not accurate. That is probably the total number of properties listed and includes hosted properties (where an owner is at home and only lets out a room or studio), as well as casual renters who only let out during holidays. Permanent HL homes have been estimated at around half that figure.

As I have outlined in previous newsletters, Airbnb and other platforms are among the myriad problems contributing to the housing crisis. It seemed that STRA was viewed as low-hanging fruit in addressing the housing crisis, when in reality it is a much more complex problem with many layered issues. This is a list of the top ten reasons for how we got into this mess:

10 REASONS WHY WE ARE IN A HOUSING CRISIS

- Insufficient supply: We currently have a decrease, not an increase, in new construction.

- Archaic, complex and convoluted Planning Regulations, especially in NSW.

- Taxation and investment incentives have skewed housing into an investment vehicle.

- The sell-off of social housing and the failure to build more.

- The DA approval process is weighted in favour of existing residents (NIMBYs) over incoming residents.

- More people are living alone, and fewer people live in larger houses.

- The rise of short-term letting platforms like Airbnb.

- Urban sprawl is less desirable. People want to live near transport and infrastructure.

- Immigration.

- The lack of the “missing middle”, or diversity in housing choices.

It is interesting to note that the two on the list that are possibly the most easily addressed have become the most politicised. Holiday letting is something that local LGAs can address, so it became a target, or perhaps a scapegoat. Immigration is now a hot-button issue and is being used by a variety of right-wing organisations. There was no change in the housing crisis during COVID when Australia had zero immigration.

All of the ten reasons, and more, above need to be addressed together. There is no quick fix, and this is a problem that took over 20 years to create and will take at least that long to fix.

It’s a waste of time and resources. People want to rent air BnB s in the area. It doesn’t help the housing crises at all.